A developer journey map is a simple way to see why developers go away before they even try your product.

This happens because developers can't find the right proof fast enough, the first success moment takes too long, and the answers live in five different places.

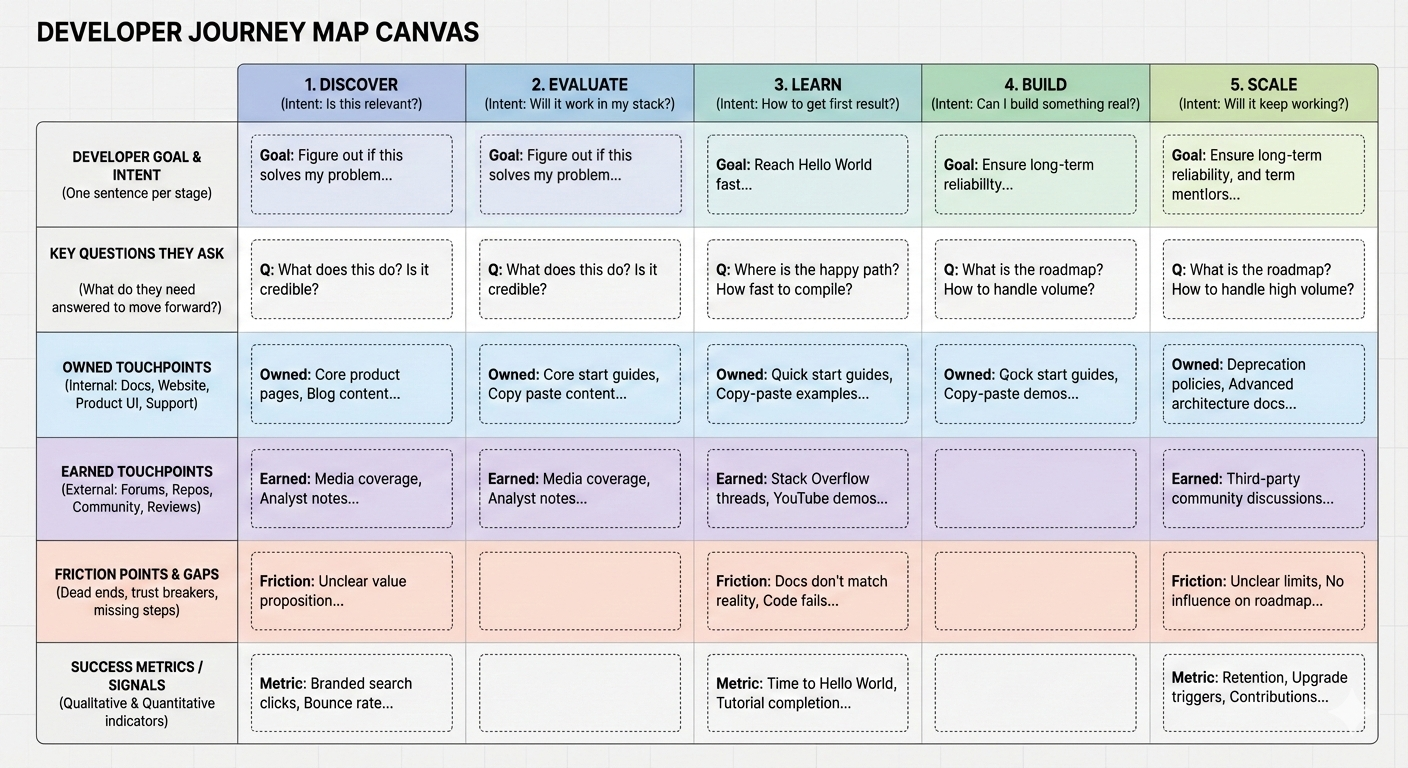

The map fixes that. It gives you one view of the whole experience, across every touchpoint, inside and outside your product, so you can remove friction and speed up adoption.

What is a developer journey?

A developer journey map is a visual model of how developers discover your product, evaluate it, learn it, build with it, and scale with it. It's a customer journey developer intent and developer behavior.

The goal of a developer journey map is simple: it helps you stop guessing why developers get stuck. It shows you what a developer is trying to do at each step, what questions they need answered to continue, and where those answers should live.

Once you see the missing answers and broken paths, you know exactly what to fix first so more developers reach a working result and keep using the product.

Done well, it becomes a practical alignment tool across DevRel, Product, Support, Marketing, and Sales, because everyone can point to the same map and agree on what "broken" looks like.

For example, Support might say "People keep asking how to handle rate limits", the docs' owner might say "We mention it in one place", Engineering might argue "It is not obvious in the API responses", and Marketing might not mention it at all.

The map turns that into one clear action: add a rate limit section in the quickstart, show a real error example, and link it from the pricing and limits pages.

Difference between a marketing funnel and a developer journey

A marketing funnel describes what the company wants a person to do, like visit, signup, convert. Meanwhile, a developer journey describes what the developer is trying to achieve, like understand, test, implement, ship, and scale.

Use a funnel when you are optimizing company outcomes (like improving signup conversion or onboarding emails), and a developer journey map when you are optimizing the real experience (building with your product, especially when developers can succeed or fail without talking to anyone).

Here's the easiest way to see the difference:

A funnel might say "drive more signups", while a developer journey map asks "What does a developer need to see and do before they are willing to bet a real project on this tool?" That second question is where adoption is won.

The five stages of the developer journey

Most frameworks follow these five stages: Discover, Evaluate, Learn, Build, and Scale.

Developers don't move through these stages on a timeline like "day 1, day 7, day 30". They move when they get a reason to take the next step.

Imagine a backend engineer who sees your tool on GitHub, skims the docs for two minutes, then closes the tab because they are busy. Two weeks later, they hit the exact problem your tool solves, come back, try the quickstart, and get a working request.

That's a normal journey.

The stages describe what they are trying to accomplish in each moment, not how many days have passed.

1. discover

A developer hears about your product from a teammate, a tweet, or a GitHub mention. They open your site, and in ten seconds they decide one thing: "Worth a deeper look" or "Not for me." At this point, they aren't trying to buy. They are trying to quickly understand what the product does and whether it's legit.

This stage works when the first page they land on makes the product solution obvious, shows a technical proof point fast, and gives them a clear next click depending on what they want. For example: "See a working request", "Check supported languages", or "Read the limits".

Now you can list the places they will look first. Typical first stops include your developer hub page, a core product or use case page, and a quick example that shows input and output. Sometimes they'll also look outside your site quickly, like GitHub or community mentions, especially if they don't trust marketing pages.

2. evaluate

A developer is now thinking: "Will this work for me, in my stack?" They are looking for constraints and deal breakers.

For example: authentication method, rate limits, data retention, pricing, and what happens when something fails. This stage succeeds when you show real implementation details, not just promises.

Common places they check are your docs entry pages, limits and pricing information, security notes, real examples, and external validation like repos, issue threads, or community Q and A.

3. learn

The developer tries to get to a first working result. If they can't reach the first working result quickly, most will quit or postpone.

This stage succeeds when the quickstart is genuinely quick, examples run without surprises, and there's a clear "I am stuck" path that doesn't require begging for help.

They typically bounce between quickstarts, code samples, troubleshooting, and whatever support channel is easiest to access.

4. build

Now they're implementing a real workflow, not a demo. This is where questions become practical: retries, debugging, production readiness, monitoring, and support quality.

This stage succeeds when you make production patterns easy and remove hidden complexity.

They spend time in deeper docs, reference guides, changelogs, SDK docs, and support threads.

5. scale

Usage grows, stakes increase, and the developer wants confidence. They care about reliability, change management, deprecations, and whether the product will grow with them.

This stage succeeds when changes are communicated clearly, scaling guidance is real, and advanced paths exist.

They look for roadmap signals, scaling docs, support escalation, and community or advocacy paths if you have them.

Developer journey touchpoints: Owned vs earned

A simple way to keep this sane is to split touchpoints into two buckets:

Owned touchpoints

Teams often start by mapping the company-owned touchpoints first because they're easier for inventory, easier to change, and easier to measure, such as your website, docs, product UI, onboarding, code samples, support, pricing, and your social presence.

Earned touchpoints

These are the places you influence but don't control: GitHub discussions in forums, third-party communities, media coverage, analyst notes, meetups hosted by others.

Most teams map only owned touchpoints because it's convenient. That's also why they miss where trust is actually won or lost.

Best practices for building a developer journey map

You don't need a perfect process. You need a workshop, a real developer lens, and a willingness to document uncomfortable gaps.

Set up a short working session

Block roughly four hours. Invite people who see different parts of the journey, like DevRels, marketers, and even salespeople.

If you can include a couple of developers, customers or not, you'll learn ten times more.

Pick one developer persona and one target use case

If you try to map everyone, you map no one. Pick a primary persona, for example a backend engineer integrating an API. Then pick a specific use case that matters, for example "send events to our system and query them."

Finally, define what success looks like in concrete terms, like "First working integration in staging". That success definition becomes the anchor for the entire map because it tells you what "progress" actually means.

Here's a detailed guide on how to create a developer persona along with a template.

Write developer goals for each stage

These should be developer goals, not company goals.

- Bad: "Convert to signup".

- Good: "Figure out if this solves my problem and if I can trust it".

Use the five stages and write one sentence per stage.

Write the key questions developers must answer

This is where the map becomes actionable.

Examples:

- Discover: What does this do, is it credible, is it for my use case?

- Evaluate: Will it integrate with my stack, what are the limits, what does it cost?

- Learn: How fast can I reach Hello World, what is the happy path?

- Build: What breaks in production, how do I debug, how do I get help?

- Scale: What happens at higher volume, what is the roadmap, how do changes get communicated?

List your owned touchpoints and place them where they first matter

Be specific. "Docs" is not a touchpoint, "Quick start for Node" is.

Map every key owned asset you control, then place it in the stage where a developer would first need it.

If you are unsure, do a walkthrough like a new developer: start from a blank browser, search your product name, click what looks most credible, and try to reach a working result.

As you go, write down what you touched, what you expected to find, and what was missing or confusing.

List external touchpoints and where developers validate you

This is usually the biggest blind spot. Include the places developers trust more than your website, like GitHub repos and issues, Stack Overflow threads, Reddit and Discord discussions, YouTube demos and reviews, and external blog posts or community guides.

Then ask: if a developer reads only these external touchpoints, do they trust you more or less?

Mark friction points and prioritize fixes

Friction is any moment where a motivated developer can't move forward.

It often shows up as missing steps, docs that don't match the product, example code that fails, unclear limits or pricing, no obvious path to support, or confusing onboarding flows.

Once you have a list, prioritize fixes with a simple rule: first fix anything that blocks first success, then what causes repeated support tickets, followed by what breaks trust, especially in external touchpoints where you can't control the narrative.

Conclusion

A developer journey map is a practical way to make product adoption easier. Pick one persona, pick one use case, run a four-hour mapping workshop, and fix the top three friction points blocking first success. That is where the compounding starts.

If you want to avoid making costly mistakes when creating your developer customer journey and need guidance or help in building one, drop me a message on LinkedIn or schedule a consultation call.